- Chronicle

Seating in public gardens

A custom and a service

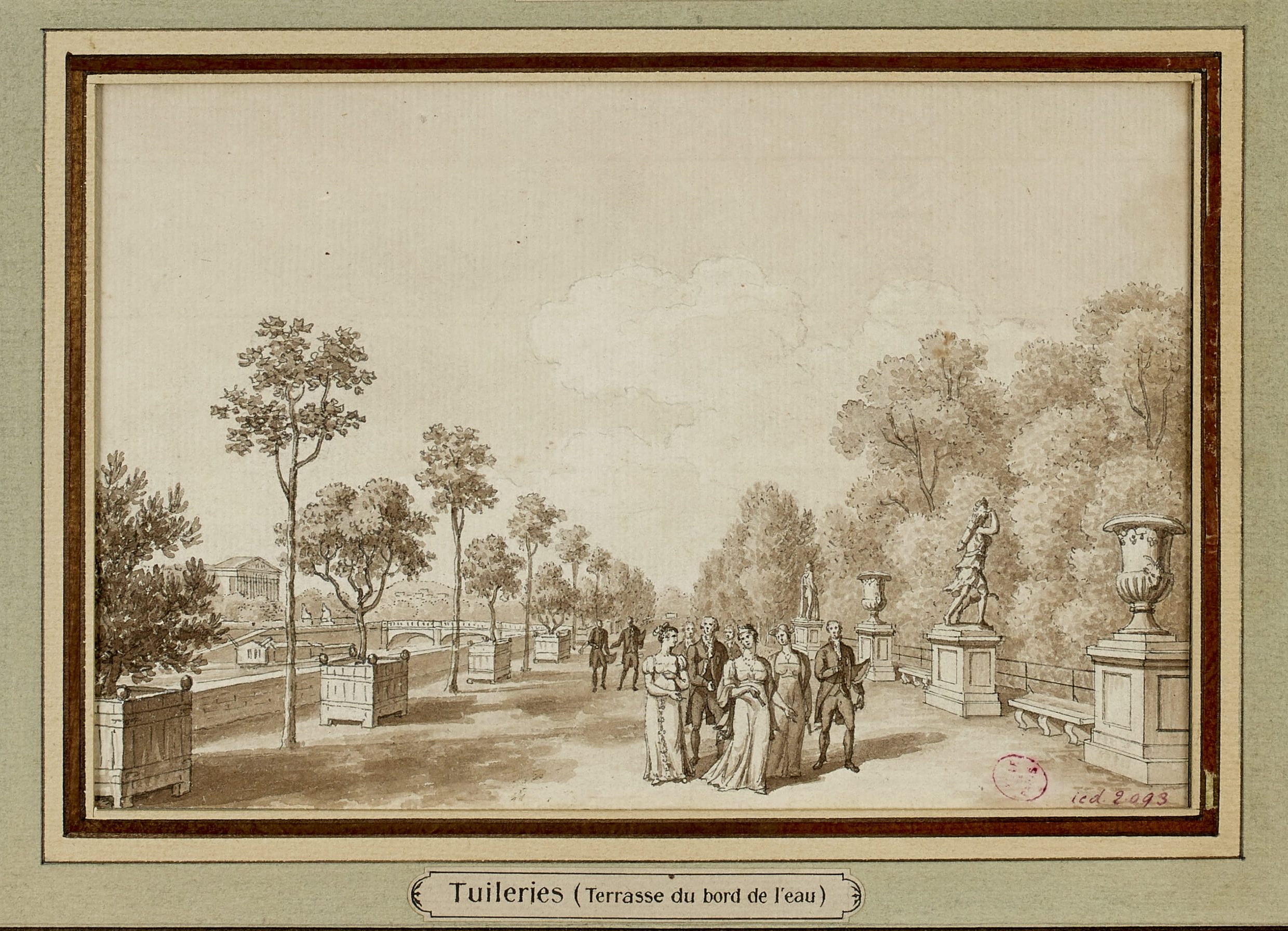

The Tuileries Garden was one of the first – if not the very first – in the world to make seating available to the public. Until the early 17th century, chairs and benches were not standard features of public gardens. The very idea of a ‘public’ garden was unheard of, as the great parks of Paris – Tuileries, Luxembourg and what would become the Jardin des Plantes – belonged to the king, and were only frequented by the royal family and their entourage. When André Le Nôtre completed the Tuileries Garden, Louis XIV’s Chief Minister Colbert decided to leave it open to all. This ‘all’, however, only referred to a certain type of visitor, with guards denying entry to ‘servants’ and ’scoundrels’. A few wooden benches were installed at the time; by the end of the century, they numbered almost two hundred.

Sitting in the Tuileries Garden was part of a new ritual – namely, the urban walk, which has recently been studied by historians like Daniel Rabreau and Laurent Turcot. The function of these walks was both social and sanitary, the objective being to ’see and be seen’ while enjoying the ‘fresh air’.

The ritual later spread to the burgeoning grands boulevards, where the first stone benches, fashioned after those of Parisian gardens, were set up in 1751. Diderot and D’Alembert’s Encyclopédie, first published in 1782, deemed the provision of benches in public spaces a ‘necessity’.

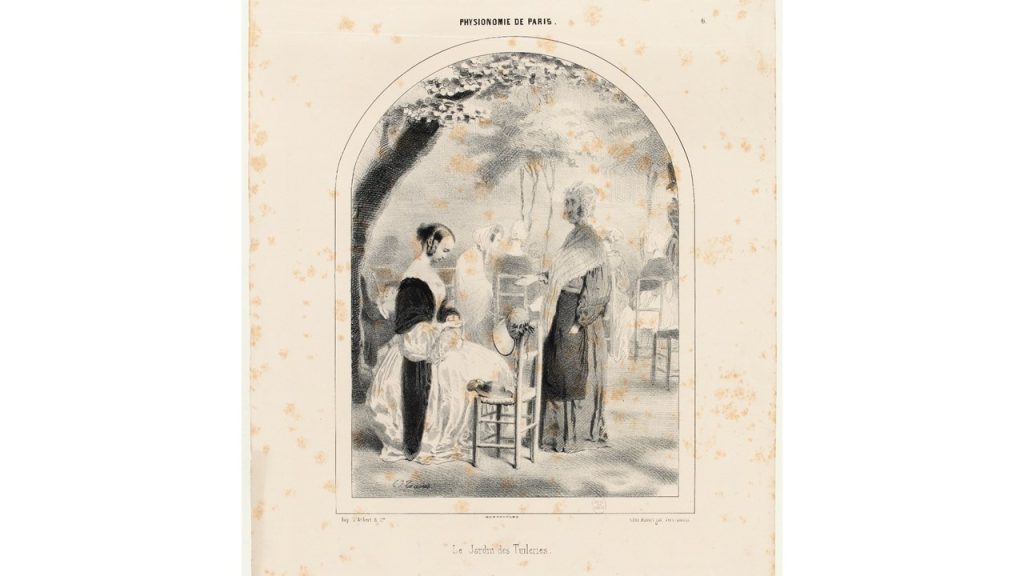

But lo and behold, free seating had already become a thing of the past – even at the Tuileries Garden. This decision was made in 1767 by Governor Bontemps, who went so far as to hire ‘chaisières’ (chair attendants) to collect the rental fee: as soon as one took a seat, an attendant would come to ask for a coin. Free seating would not return until 1970.

Découvrez les

Chroniques du Jardin

- Chronicle